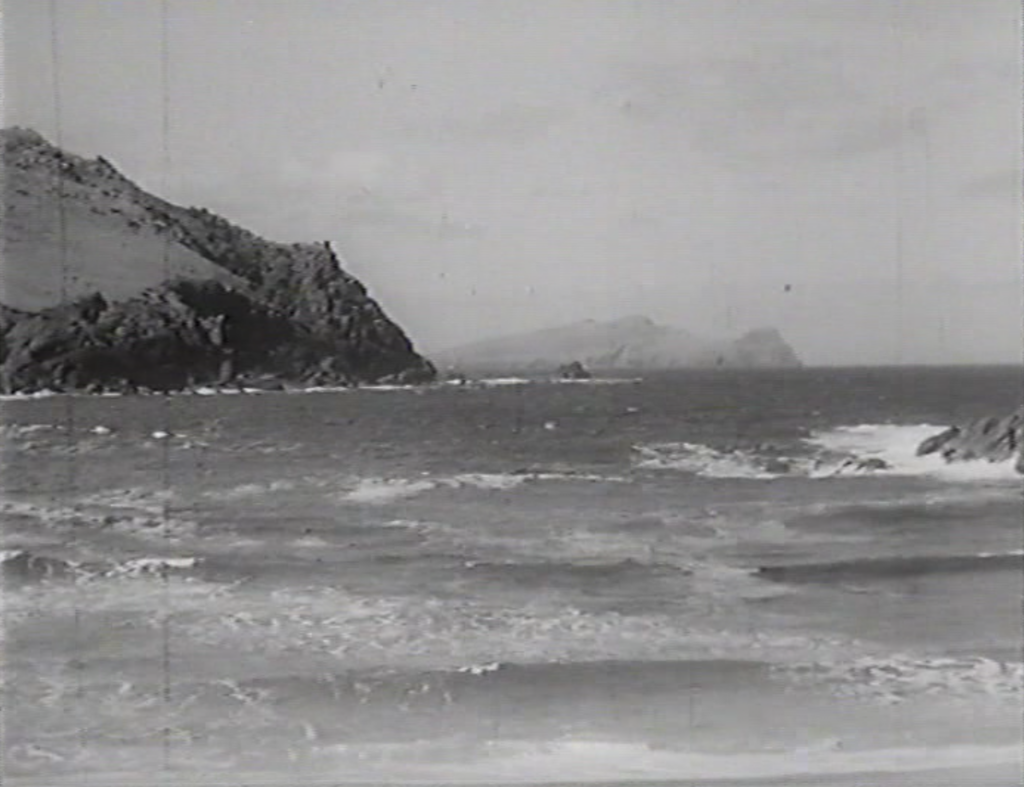

West of Kerry - Clogher Beach

Trá Chloichir

|

Trabaneclogher

Address

Cloichear, Dún Urlann, Corca Dhuibhne

52.156724

, -10.459758

Briefly used in establishing shots because of its artistic framing of Inis Tuaisceart, Clogher Beach is a well-known attraction on the road from Dún Chaoin to Baile an Fheirtéaraigh. It also features in the film Tarrac. The beach itself is home to bright yellow ochre cliff faces, and a number of fossils from the Silurian period (430 million years ago) can be seen in the blue-grey siltstone.

Curiously, this film is known by at least four titles, The Islandman, West of Kerry, Men of Ireland and Eileen Aroon. Following The Dawn (Tom Cooper’s unexpectedly successful film about Irish republicanism from 1935, which was shot on a shoestring budget on location in Killarney), West of Kerry / The Islandman is a reminder of what could have been, and very nearly was: the nascence of an indigenous Irish film industry – Kerry-based, no less – in the early sound era, a full fifty years before the establishment of the first Irish Film Board.

As Lorcán Ó Cinnéide recounts in the accompanying interview here, West of Kerry is hardly strictly faithful to the language and culture of the community it depicts. Few, if any, extras from the community are used; the song and dance sequences that are stacked between narratives scenes (awkwardly, from today’s standards, but typical of an earlier “cinema of attractions” which prioritized the presentation of a series of entertainments over linear narrative storytelling) also do not feature any local-to-the-area performers. The storyline itself is clearly suited to supporting by-then already-clichéd associations of rural (and, importantly, Catholic) life as “really” Irish versus urban and east-coast society as Anglo-lite, debauched, Protestant, and comparatively soulless. Here, a Trinity student falls in love with “traditional” Irish life, embodied by a traditional Irish-speaking girl out on the Great Blasket Island; said student ultimately gives up his worldly ways in favour of a simpler, nobler lifestyle and settles down with the girl. Unlike The Dawn, West of Kerry does not dramatize a literal war; but much like The Dawn, it dramatizes a war of ideas, ideals, and ideologies.

Notably, the film is marked both inter- and extra-textually by linguistic ideological conflict. During the early days of film distribution in Ireland – which just about includes the 1930s – there was some question over whether a national cinema – internationally recognized as an important ideological and propagandistic tool – could be fully realized in an Anglophone context. According to film historian Kevin Rockett, after the Irish Film Society was established in 1936 in response to a “loss of European cinema” after Irish independence from Britain (Cinema and Ireland, 51), the political party in power, Fianna Fáil, redirected media dependency towards Anglo-American film distributors. The Gaelic League consequently protested that sound cinema was “bestowing unfair advantage on English over Irish” (52). As issues surrounding overall cultural representation gradually overtook issues of Irish language specificity over the course of the 1930s, West of Kerry represents a last gasp, of sorts, for early Irish language cinema. The film tries to have it both ways biliingually, featuring a few snippets of Irish here and there, but ultimately deprioritizing the language in favour of English narration.

A few years prior to West of Kerry, The Dawn had been conceived as an answer to suggestions that appeared in the The Irish Independent regarding the potential for film production in Ireland. Killarney resident Tom Cooper had assembled his friends, including Donal O’Cahill as a planner, co-writer and actor, to shoot the film on location and in a makeshift sound-proof studio in Killarney. O’Cahill, galvanized by the experience, thereafter established a breakaway company to make The Islandman, this time drawing on the thematic and stylistic inspirations of Robert Altman’s wildly successful, Romantic / primitivist pseudo-documentary, Man of Aran from 1934. West of Kerry provides perhaps a “softer” version of rural Ireland from a primitivist perspective. The film was criticized both for not capitalizing enough on the local scenery to “sell” its authentic Irishness, and for capitulating to the Hollywood narrative trope of romantic closure. Ultimately, none of the Kerry filmmakers, including O’Cahill, seemed focused enough on actually making films to feed the fledgling Irish national film industry, and the brief trend in Kerry-based productions died. West of Kerry remains one of few films from this brief but fruitful era in early indigenous Irish filmmaking, which was nevertheless ideologically ambitious and, in this case, impressively far-flung.

Videos

Links

- » https://ifi.ie/film/monthly-must-see-cinema-west-of-kerry/

- » https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0160525/?ref_=fn_all_ttl_4

- »https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DXx-2GO-QrM

- » https://www.dingledarkroom.com/winter-sunset-at-clogher-strand-dingle/

- » https://www.irishexaminer.com/property/homeandgardens/arid-30835290.html